| Part of a series on the |

| Socialist Republic of Romania |

|---|

|

|

Relationship with the USSR |

|

Relations with other states |

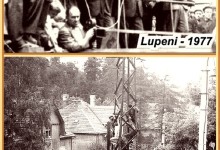

The Jiu Valley miners' strike of 1977 was the largest protest movement against the Communist regime in Romania before its final days.[1] It took place 1–3 August 1977 and was centered in the coal mining town of Lupeni, in Transylvania's Jiu Valley.

Events

[edit]Prelude

[edit]The immediate cause of the strike was Law 3/1977 (enacted on 30 June that year), which ended disability pensions for miners and raised the retirement age from fifty to fifty-five.[1][2] Other issues included the extension of workdays beyond the legal eight hours, low wages, overtime not paid since March, work on Sundays, paycheck deductions for failing to meet production targets, poor living conditions and the leadership's indifference toward their plight.

Before the strike began (and perhaps while it was going on), some miners proposed sending a delegation to the capital, Bucharest, to discuss their problems with the leadership of the Romanian Communist Party, but this option was discarded as they probably thought any split to two locations would fatally undermine their cause. During the pre-strike period and just as the strike began, certain of the sectoral party chiefs who obstructed the miners' efforts were verbally and physically assaulted by the miners.

Opening and first attempt at resolution

[edit]Of 90,000 miners in the Jiu Valley, 35,000 decided to stop working on the evening of 1 August. Those at Lupeni were immediately joined by their fellow miners from nearby locations such as Uricani, Paroșeni, Aninoasa and Petrila. A list of 17 demands, approved by the strikers as a body, was drawn up by the strike leaders, Ioan Constantin (Costică) Dobre (b. 1947) and Gheorghe Maniliuc, who were aided by Dumitru Iacob, Ion Petrilă, Dumitru Dumitrașcu, Mihai Slavovschi the engineer Jurcă and the Amariei brothers. They requested that President Nicolae Ceaușescu personally come to Lupeni to receive their demands and negotiate with them. Speeches containing demands were made and the Valley was in a state of maximum tension.[3]

Frightened by the events, on 2 August the authorities sent a negotiating team from Bucharest. Ilie Verdeț (first vice-president of the Council of Ministers) and Gheorghe Pană (president of the Central Council of the General Trade Union Confederation of Romania and Minister of Labour) were both Politburo members, Verdeț a former miner himself. Dobre, a pit brigade chief from the Paroșeni mine, later recalled Verdeț's speech (attended by some 20,000 miners), in which he stated he could not decide what measures to take but was merely there to find out about the miners' problems, which only Ceaușescu could decide to alleviate. At this point the crowd shouted, demanding Ceaușescu's personal presence, whereupon Verdeț claimed the President was occupied with "urgent party and state problems" and that if work resumed Verdeț would "guarantee" his return to the Valley within a month with a favourable reply from Ceaușescu. These promises were regarded with great suspicion by the crowd, which, emboldened, began booing again and warned that they would not go back to work until Ceaușescu personally came and publicly promised to resolve their grievances. Booed, insulted and pelted with food scraps, Verdeț and Pană hid behind Dobre and, backed up against the wall of the gatekeeper's booth, nervously begged him to assure their safety. Literally backed into a corner, Verdeț promised the miners that he would convince Ceaușescu to come.[3]

What happened next is a matter of dispute. Dobre insists that the two party functionaries were held hostage in the booth until Ceaușescu's arrival, given only water and monitored in their conversations with Bucharest;[3] other sources confirm this account.[4][5] Verdeț dismissed this version as being merely a legend.[3]

In order to avoid the possibility of violent clashes, the Jiu Valley authorities infiltrated the area with informers and Securitate members, but avoided the visible imposition of martial law, also to keep tensions down. Arms depots were guarded for fear the miners might raid them. On the day of Ceaușescu's arrival, Securitate troops as well as party functionaries were called in from Craiova, Târgu-Jiu and Deva to try to disperse the protesters.[6]

Ceaușescu speaks

[edit]

When the strike broke out, Ceaușescu and his wife Elena were on a Black Sea vacation. At Verdeț's insistence, he hastily came to Petroșani on 3 August 1977, and 35,000 people (some sources say 40,000)[6] came to see him – to be sure, not all had come to hold a dialogue with him, but went out of curiosity or carried away by events, but the audience was nonetheless impressive in size. At first, despite the charged atmosphere, some shouted "Ceaușescu and the miners!", but others yelled "Lupeni '29! Lupeni '29!" (in reference to the Lupeni Strike of 1929, enshrined in the mythology of the Romanian Communist Party), in an effort to add legitimacy to their cause.[1][6] Dobre read the list of grievances to Ceaușescu, presenting 26 demands related to work hours, production targets, pensions, supplies, housing and investments. They asked for a restoration of the status quo ante in social legislation, the guarantee of adequate food supplies and medical care, the establishment of workers' commissions at the enterprise level empowered to dismiss incompetent or corrupt managers, and a pledge of no reprisals against the strikers.[7] After that, Dobre recalled, "While my name was being shouted, I turned toward Ceaușescu, gave him the list from which I had read and he said to me: 'Thank you for informing me, comrade'. Once in front of the microphones, Ceaușescu was not allowed to speak. Some were booing him, others shouted that they wouldn't go into the mine, and from afar one could hear my name. In vain the appeals for quiet with raised arms from the activists on the podium".[3]

Visibly shaken according to Dobre,[8] Ceaușescu gave a halting 5-hour (other sources say 7-hour)[6] speech that was soon interrupted by boos. Beginning in a trembling voice, he made an initial, hopeless attempt to send the miners back to work: "Comrades, this is not the war… this is a disgrace for the entire nation… a disgrace! I have taken note of your grievances." He tried to explain the party's policy and appeal to the miners through demagogy, claiming that the party leadership had wanted to reduce working hours but that the miners had resisted, which insult to their intelligence was met by cries of "It is not us! Bandits, thieves!" A general murmur of the crowd ran through the speech, along with protests and outbursts of anger; whenever Ceaușescu began to stumble over his words, some of the men booed and whistled. Proposing that the six-hour day be introduced gradually at Lupeni and then at the other mines, the men replied, "A six-hour day from tomorrow." Toward the end, when, angered by their audacity, he still refused to grant an immediate six-hour workday, phrases loudly heckled included "He has no idea what the people's interests are" and "He is not concerned with the workers' fundamental interests". Starting to threaten them, Ceaușescu warned that "If you do not go back to work we'll have to stop pussyfooting around!"[9] According to observers, "Down with Ceaușescu!" was then heard after prolonged booing, an account confirmed by Verdeț. Only when Dobre seized the microphone and urged the miners to let Ceaușescu finish did the atmosphere become less charged. At that point he saw that his only exit lay in making conciliatory promises he had no intention of honouring; using the wooden language that miners trust, he promised to resolve their grievances (agreeing to a six-hour workday for everyone, with Saturdays and Sundays off, and to build factories that would provide jobs for miners' wives and daughters), vowed those responsible for the miners' discontent would be brought to account and that there would be no retribution,[9][10] and was applauded. Verdeț and Pană were released and the strike came to an end immediately after Ceaușescu's departure, the men dispersing and some going into the mines for the August 3 evening shift.[9] They even offered to make up the time lost during the strike.[5]

One significant slogan used during the strike was "Down with the proletarian bourgeoisie", which was targeted against the Communist functionaries who administered the Valley and profited from the miners' labour and caused their salaries to be kept down. In using it, they attacked the perceived injustice of the hierarchical Communist system with its bureaucratic nomenklatura (which existed alongside its political and repressive sides, represented by the party and the Securitate), and invoked the Communists' decades-long struggle against the bourgeoisie in an ironic sense. To them, the regime had become a state in which capitalism continued to operate, albeit in the service of a clearly delineated group of bureaucrats.[6]

Repression

[edit]The first session of the party's Central Committee after the strike took place on 4 August; it was entirely devoted to discussing the previous days' events and participants were preoccupied with finding someone to blame for what had happened. Verdeț was named at the head of a commission which investigated the strike's causes. Ceaușescu pointed the finger at "the party personnel from the region and the Mines Directorate".[3]

Repression, led by Generals Emil Macri and Nicolae Pleșiță,[11][12] took various forms. After Dobre spoke, the miners realised he would be targeted and so guarded his residence in order to prevent his arrest. He was not arrested on the spot; instead, the authorities busied themselves with identifying the miners: engineers and section heads were called to Securitate headquarters to identify them from pictures that had been taken secretly. All strikers who were party members were sanctioned or even removed from the party. Some of the miners were sent back to their native counties. Those who were considered to have been violent during the strike were tried and sentenced to 2–5 years' imprisonment through correctional labour for disturbing the public order and offending good morals. In practice, correctional labour meant internal deportation, although some strikers did go to prison. The miners were intimidated and attacked, along with their families in certain cases. Miners who were questioned were insistently asked never again to strike or speak out against the party. Many strikers were called to the Petroșani Securitate building, where they were repeatedly mistreated during interrogations by, for instance, being beaten over the head and having their fingers bound to doors.[6] The ensuing investigation tried to discover where the core of support for the strike lay, and while some 4,000 workers were moved to other mining areas in the following months, others were said to have ended up in labour camps on the Danube-Black Sea Canal.[9] The main strike leaders disappeared within weeks, with other outspoken miners rounded up piecemeal and dispersed over the next few months. The concessions held long enough for the authorities to break the organisational backbone of the resistance, but eventually most of these were withdrawn and the eight-hour workday imposed, though this was not made official until 1983.[5]

In the party-led meetings that followed the strike, the protesters were labelled "anarchist elements", "base" and "worthless people". At trial they were called "Gypsies", "lowlifes", "impostors" and "infractors". At least 600 miners were interrogated; 150 penal dossiers were opened; 50 were hospitalised in psychiatric wards; 15 were sentenced to correctional labour and actually imprisoned, while a further 300 or more (who were considered dangerous) were internally deported. Almost 4,000 were fired on the pretext that there was no work, or else the smallest dispute with or protest against the mine management was used to sack them. Several hundred families were moved out of the area. After prison or deportation, several former protesters continued to be harassed by the Securitate; one man, disappointed at the outcome of events, became a monk after his release from prison. The area was surrounded by security forces; two helicopters were brought in to monitor happenings and ensure a tight link with Bucharest, although the official reason for their presence was to fly mining accident victims to the hospital.[6]

The number of Securitate and Militia forces at Petroșani was doubled and military units were placed near all mines in the Jiu Valley. Securitate agents were hired as miners, not only to inform on other workers, but also to exert psychological pressures on them and even beat them before witnesses so as to create a climate of intimidation. Writer Ruxandra Cesereanu claims a relatively large number of common criminals released from prison were brought into the mines as well. The Valley was declared a restricted area from 4 August until 1 January 1978. Strict surveillance was intended to block the flow of any information to the rest of the country or contact with the outside world, yet 22 miners acting on behalf of 800 others managed to send a letter (dated 18 September) to the French newspaper Libération, which published it on 12 October. Foreign media drew a link between Paul Goma's movement that spring and the miners' unrest several months later,[6] though no connection actually existed.[13]

Aftermath

[edit]The response to the unrest—giving the appearance of acquiescing to the workers' demands and meeting local grievances, then isolating the ringleaders by sending them away or imprisoning them once the strike had ended, and reneging on concessions—established a model for dealing with such incidents in the future. For example, other disturbances followed in Cluj-Napoca, Turda and Iași, where students and workers in two separate protests apparently marched through the streets to party headquarters. There was a strict news blackout on such events, but it seems these were peacefully and easily defused given the non-political nature of the demands (poor factory and dormitory conditions) and their timely resolution.[4] The Jiu Valley strike, along with the Goma episode, taught dissidents that any public deviation from the regime would not be tolerated.[14]

Gheorghe Maniliuc was imprisoned for three and a half years, and after his release died in 1987 of heart trouble.[15] Dobre's fate was long a source of speculation – even the first version of the Tismăneanu Report claimed he had been killed,[16] while others theorised he became a party activist, was put in a mental hospital, etc.[6] Dobre gave an interview in 2007 in which he clarified later events. The salient points of his later life are as follows: he and his family were moved to Craiova on August 31, 1977, where they lived until May 1990, in total isolation and under constant Securitate surveillance until December 1989 (over 50 agents informed on him). He was given work as an unskilled auto mechanic and, after a calculated rejection from other universities, he attended the Ștefan Gheorghiu Academy in the 1980s. Dobre claimed he never authored Communist propaganda and that he showed a rebellious attitude toward the faculty. He repeatedly asked to be permitted to emigrate but was refused, and holds the Securitate responsible for the 1979 airplane crash that killed his brother, a pilot. During the Revolution, Dobre claims he was hailed by a crowd in Petroșani and appeared on television but was sidelined due to his hostility toward the National Salvation Front, being labelled an "extremist" and a "terrorist", particularly in the Craiova and Jiu Valley newspapers. In spring he moved to Bucharest, but soon the June 1990 Mineriad broke out. Though Dobre claimed he barely managed to hide from a group of armed miners looking for him, around the time he become an employee of Romania's Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He arrived with his family in London as an employee of the Romanian embassy that September and afterwards demanded asylum; he would be later sentenced by Romanian court to five years' imprisonment in 1992 for running off with the embassy's funds. Dobre was granted asylum in 1994 and became a British citizen in 2002.[17]

Legacy

[edit]

Dobre sees the strike as a "prelude" to the events of December 1989.[17] According to writer Ruxandra Cesereanu, communist leaders feared the movement could "break the myth of unity between the Communist Party and the working class". Cesereanu considers that the strike offered an "exercise in democracy": for almost three days, miners demanded and protested before a microphone; they spoke freely, none were excluded and no censorship was imposed. Those investigating the miners who had been arrested perceived the strike as an "uprising", frequently using this term during interrogations. Noting the miners were part of a social class until then supposed to be an ally of the party, Cesereanu believes the apparent break with workers frightened the leadership, which could depend even less upon the peasants (then being forced into agricultural cooperatives) or the intellectual élite (part of which at the time was chafing under the rise of protochronism heralded six years earlier by the July Theses). Ceaușescu himself appeared stricken; as his near-fainting episode indicates, he was not prepared for the outbreak of dissent and had seen that the regime was not as stable as he might have believed.[6] It was, Verdeț said, "the first self-abasement of Ceaușescu's political career."[3]

The strike—probably the first workers' protest since 1958, with the exception of a September 1972 strike in the Jiu Valley[18]—began not as an anti-Communist or even an anti-Ceaușescu movement but rather a socio-economic one in spontaneous reaction to the new pensions law, as confirmed by the miners' inexperience, which led them to improvisation and hasty decision-making. However, once the Communist leaders were sequestered, it moved in a political direction and, given the repression that followed, was interpreted as such by the authorities. Cesereanu believes the strike did have an intrinsically political character in the sense that the miners—thought of as essential components of the Communist working class—revolted against their ideological bosses and conditions created by the very political system that used them as part of its labour force. So while collective and unpremeditated, in Cesereanu's opinion the protest challenged the Communist leadership of the day and ultimately the regime itself.[6]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b c Deletant, p. 243

- ^ Petrescu, p. 156

- ^ a b c d e f g Mihai, "Greva..."

- ^ a b Siani,-Davies, p. 35

- ^ a b c Ramet, p. 144

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Cesereanu

- ^ Ramet, p. 143.

- ^ Dobre elaborated: "Ceaușescu betrayed a visible and confused state of nervousness, worry, aggressiveness and venality. You could read on his face the shock and worry at how he had been received. I saw nothing in him of the propagandistic descriptions of a bold, courageous, dignified individual, righteous and full of humanity. From the time he appeared next to me and from the deafening and repeated cries of "We will not enter the mine!", Ceaușescu was wringing his hands, rocking on each foot and looking questioningly at his people, as if asking for help; he mumbled nervously, nonstop and in a soft voice. In Mihai, "Greva..."

- ^ a b c d Deletant, p. 245

- ^ University of Southern California School of Politics and International Relations. Studies in Comparative Communism, p. 294. 1992, Butterworth-Heinemann.

- ^ Vlad Stoicescu (2009-09-30). "'I-am ucis, bineînțeles. Asta făceam noi' ('I Killed Them, of Course. That's What We Did')". Evenimentul Zilei. Archived from the original on 2009-10-02.

- ^ Ilarion Țiu (2009-09-30). "Generalul Pleșiță a fost condus pe ultimul drum de foști subalterni din Securitate (General Pleșiță Was Led Down His Last Path by Former Securitate Subordinates)". Jurnalul Național. Archived from the original on 2009-10-03. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

- ^ Petrescu, p. 146.

- ^ Roper, Steven D. Romania: The Unfinished Revolution, p. 55. Routledge, London, 2000, ISBN 90-5823-027-9

- ^ (in Romanian) Victor Roncea, ["Ucis de Comisia Tismaneanu" ("Killed by the Tismăneanu Commission")], in Ziua, January 8, 2007

- ^ Mihai, "Dobre..."

- ^ a b Mihai, "Eroul..."

- ^ Petrescu, p. 146, 155.

References

[edit]- (in Romanian) Ruxandra Cesereanu, "Greva minerilor din Valea Jiului, 1977" ("The Jiu Valley Miners' Strike, 1977"), in Revista 22, Nr.752, August 2004

- Deletant, Dennis, Ceaușescu and the Securitate: Coercion and Dissent in Romania, 1965-1989, M.E. Sharpe, London, 1995, ISBN 1-56324-633-3

- Florin Mihai,

- (in Romanian) "Greva minerilor din Valea Jiului" ("The Jiu Valley Miners' Strike"), in Jurnalul Național, March 5, 2007

- (in Romanian) "Eroul din '77, azil politic in Anglia" ("The Hero of '77, Political Asylum in England") Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine, in Jurnalul Național, April 11, 2007

- (in Romanian) "Dobre a fost declarat mort de Tismăneanu" ("Dobre Was Declared Dead by Tismăneanu") Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, in Jurnalul Național, April 12, 2007

- Petrescu, Cristina in Dissent and Opposition in Communist Eastern Europe, ed. Detlef Pollack, Jan Wielgohs, Ashgate Publishing, London, 2004, ISBN 0-7546-3790-5

- Ramet, Sabrina. Social Currents in Eastern Europe: The Sources and Consequences of the Great Transformation, Duke University Press, Durham, 1995, ISBN 0-8223-1548-3

- Siani-Davies, Peter. The Romanian Revolution of December 1989, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 2005, ISBN 0-8014-4245-1

- (in Romanian) Chronology of Dobre's life, from Ziua

Greva minerilor din Lupeni a avut loc în august 1929 ca rezultat al eșecului unor îndelungate negocieri legate de salarizare și condiții de muncă. Aproximativ 6000 de muncitori au fost implicați[1] în protestul provocat de salariile de mizerie și sărăcia extremă[2] în care trăiau minerii transilvăneni, deznodământul confruntării fiind că 68 de mineri au căzut sub gloanțele trupelor armatei române trimise de către guvernul țărănist să reprime protestul, dintre care 28 au decedat pe loc, mulți dintre ei împușcați fiind în spate[3].

Context și desfășurare

[modificare | modificare sursă]

Istoria grevelor și mișcărilor sociale din România antebelică arată ca acestea au fost întotdeauna reprimate brutal, guvernul apelând, dupa modelul masacrului țăranilor din 1907[4], la armată și măsuri brutale de reprimare a oricărui protest cu revendicări sociale[5][6]: de exemplu, greva din București în decembrie 1918 a fost reprimată de armată tot cu arme de război (mitraliere, tunuri)[7], greva generală din 1920, care cerea demilitarizarea întreprinderilor și dreptul muncitorilor de a se organiza în sindicate și de a face în mod legal grevă fiind și ea neutralizată în mod similar.[8] În materie de reacție la greve, sau la orice protest contra oligarhiei industriale și financiare care dorea să acapareze statul și să-l folosească exclusiv întru servirea propriilor ei interese[9], când nu era implicată direct, armata - principala dar nu și singura forță de represiune internă a guvernului - sprijinea acțiunile grupurilor huliganice de extremă dreaptă, care ele încercau spargerea grevelor[10] sau suprimarea libertății presei.[11]

Reacția guvernului la greva de la Lupeni din 1929 nu a fost diferită, în ciuda faptului că pentru prima dată la putere se afla un partid țărănist, și că proprietarii minei erau bancheri și politicieni marcanți ai Partidului Național Liberal. Presa internațională din acea vreme reflecta declarațiile unor membri ai guvernului, care susțineau că directoratul companiei a respins toate revendicările minerilor, adesea fără temei justificat, motiv pentru care întreaga responsabilitate revenea acestuia[12], conducerea companiei aflându-se în mâinile unor influenți bancheri liberali printre care și Gheorghe Tătărescu.[13]

Pe 5 august 1929 minerii decid să intre în grevă, conflictul afectând mai multe mine. Prima zi se desfășoară pe fundalul lipsei de reacție din partea forțelor de represiune, asta deși ziua se încheie cu oprirea grupului electric al unui puț (fapt care punea în pericol de inundare galeriile, minerii aflați în subteran riscând în plus sufocarea în lipsa funcționării ventilației) de către elementele radicale dintre greviști.

A doua zi administrația locală apelează, conform practicii vremii, la armată, care deschide focul contra greviștilor deciși să reziste cât timp nu le sunt satisfăcute revendicările, câteva zeci de mineri murind pe loc. Presa internațională a vremii vorbește chiar și despre 200 de răniți,[14][15] care și pe patul de spital fiind, sunt păziți de armată, care respinge cu baionetele miile de mineri adunați afară.

Pe 9 august sicriele celor decedați sunt purtate de căruțe de cărat bălegar spre cimitir, armata forțând cortegiul funebru să grăbească pasul.[16] Mulțimea imensă lângă cimitir a fost îndepărtată la mai multe sute de metri, iar la patru ore după înmormântări o companie de infanterie încă mai păzea cimitirul cu armele în poziție de tragere. După înmormântări, s-a declarat stare de asediu, hotelurile și restaurantele fiind închise, vânzarea de alcool interzisă, toată populația fiind obligată să fie în casă înainte de ora 8 seara.

Se înregistrează 25 de dispăruți[17], drept pentru care armata continuă pentru un timp să caute în pădure corpurile răniților grav despre care se știa că s-au refugiat, panicați, acolo, însă fără succes până în data de 9 august cel puțin, când încă se mai fac arestări și trenurile cu trupe încă mai sosesc în regiune.

Istoriografia din epoca comunistă a încercat să revendice pentru mișcarea comunistă sau PCR un rol important în protestul minerilor de la Lupeni, iar în contemporaneitatea postcomunistă anumiți istorici români reiau și ei, din motive ideologice opuse, același mit. Istorici occidentali precum Francisco Veiga resping însă teza, arătând că nu e necesară inventarea de motivații și acțiuni politice cât timp motivațiile economice erau mai mult decât suficiente pentru a explica explozia socială, cu atât mai mult cu cât pe eșichierul politic românesc la stânga centrului nu se afla „decât un gol”[18]: în contrast cu situația din unele state occidentale, comuniștii români erau paralizați în mod durabil de represiunea regimului, în plus în cazul conflictului de la Lupeni convinși fiind că este vorba despre o provocare, s-au abținut să sprijine activ greva.[19]

Vezi și

[modificare | modificare sursă]- Cea mai cumplită grevă a minerilor din Valea Jiului: vânătoarea de oameni din Lupeni, din '29. „Cadavrele erau niște grămezi de carne înșirate pe niște paie“, Daniel Guță, Adevărul, 11 mai 2015

- Greva minerilor din Valea Jiului din 1977

- Golgota (film) (1966)

Note

[modificare | modificare sursă]- ^ În august 1929 a izbucnit, în importantele mine de la Lupeni, din Transilvania, o grevă violentă, în aparență pentru motive salariale, în care au fost implicați vreo 6 000 de muncitori. - Francisco Veiga, Mistica Ultranaționalismului: Istoria Gărzii de Fier, 1919-1941, ed. II, Editura Humanitas, 1995, p. 104.

- ^ Se pare că vina pentru conflict nu se află în întregime de partea greviștilor. M. Ioanițescu, președintele Camerei Deputaților, a declarat că atât cauza grevei cât și a tragediei masacrului o reprezintă sărăcia cruntă în care trăiesc muncitorii prost salarizați din Lupeni. - "RIOT DEATH TOLL RISES AT RUMANIAN MINE: Number of Strikers Killed by Soldiers, First Put at 16 Now Said To Be 40", Special Cable to THE NEW YORK TIMES. New York Times (1923-Current file); Aug 8, 1929; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times (1851-2009), pg. 25.

- ^ Unitățile militare trimise în zonă au făcut uz de arme fără discriminare și în mod brutal: în zece minute au căzut sub gloanțe 68 de mineri, dintre care 28 au murit pe loc, mulți dintre ei fiind loviți în spate. [...] În august 1929 a izbucnit, în importantele mine de la Lupeni, din Transilvania, o grevă violentă, în aparență pentru motive salariale, în care au fost implicați vreo 6 000 de muncitori. - Francisco Veiga, Mistica Ultranaționalismului: Istoria Gărzii de Fier, 1919-1941, ed. II, Editura Humanitas, 1995, p. 104.

- ^ Brutalitatea polițienească, fără nici o deosebire, împotriva oricărui posibil dușman al ordinii politice stabilite era o practică foarte răspîndită în statul român și în altele asemănătoare din toată Europa, în care regimul liberal-burghez nu era sprijinit de un amplu consens social; […] În România, manifestarea cea mai dramatică fusese omorîrea țăranilor în 1907, dar, fără să se ajungă la astfel de extreme, bătaia, arestările arbitrare, traficul de influență și corupția de tot felul erau probleme de rutină. - Francisco Veiga, Mistica Ultranaționalismului: Istoria Gărzii de Fier, 1919-1941, ed. II, Editura Humanitas, 1995, p. 78.

- ^ În continuare, aceasta va deveni o practică obișnuită. - Francisco Veiga, Mistica Ultranaționalismului: Istoria Gărzii de Fier, 1919-1941, ed. II, Editura Humanitas, 1995, p. 45.

- ^ Ajuns la putere, generalul a jucat toate cărțile posibile, de preferință pe cea a represiunii fără menajamente împotriva oricărei manifestații sau revendicări stîngiste sau, pur și simplu, populare. Arbitrajul obligatoriu al conflictelor de muncă și militarizarea căilor ferate au fost simple aproximări ale marii capodopere, adică dezarticularea grevei generale din octombrie 1920, la care a contribuit și cenzura completă; de asemenea armata defila pe străzi cu fanfară, pentru a impresiona. - Francisco Veiga, Mistica Ultranaționalismului: Istoria Gărzii de Fier, 1919-1941, ed. II, Editura Humanitas, 1995, p. 47.

- ^ […] în decembrie 1918, la București, a fost reprimată prin folosirea masivă a trupelor de pușcași și chiar a mitralierelor și tunurilor mici. - Francisco Veiga, Mistica Ultranaționalismului: Istoria Gărzii de Fier, 1919-1941, ed. II, Editura Humanitas, 1995, pp.44-45.

- ^ Avînd în vedere pasivitatea germanilor, trupele române au expulzat de pe teritoriul lor resturile armatei ruse, bolșevici sau nu; și, la sfîrșitul războiului, au întors armele, fără șovăire, împotriva mișcării muncitorești, întîia manifestație serioasă desfășurată după război, în decembrie 1918, la București, a fost reprimată prin folosirea masivă a trupelor de pușcași și chiar a mitralierelor și tunurilor mici. Lovitura a fost chiar zdrobitoare în octombrie 1920, cînd a fost neutralizată o grevă generală care sprijinea unele revendicări ale Partidului Socialist Român - demilitarizarea unor întreprinderi, libertatea de organizare și dreptul la grevă; și, în plus, cu această ocazie au fost închiși marea majoritate a liderilor partidului. În continuare, aceasta va deveni o practică obișnuită. - Francisco Veiga, Mistica Ultranaționalismului: Istoria Gărzii de Fier, 1919-1941, ed. II, Editura Humanitas, 1995, pp.44-45.

- ^ În România, în ianuarie 1922, liberalii au revenit la putere, cîștigînd apoi fără probleme alegerile, două luni mai tîrziu. Nu mai făceau eforturi pentru a ascunde că își propuneau să ia toată puterea în stat și să-1 remodeleze conform nevoilor oligarhiei industriale și financiare. Era un stil politic direct și fără compromisuri, caracteristic și pentru alte epoci, astfel încît părea că „normalitatea” era asigurată și chiar se putea reveni la vechile timpuri de dinainte de război. - Francisco Veiga, Mistica Ultranaționalismului: Istoria Gărzii de Fier, 1919-1941, ed. II, Editura Humanitas, 1995, p. 53.

- ^ Cu toate acestea, începînd din februarie 1920, grupul a acționat în forță. Cele două acțiuni mai importante sînt încercările de a sparge grevele care paralizau fabrica Regia (Monopolurile Regale ale Statului, de fapt o fabrică pentru tutun) și atelierele feroviare ale orașului Iași. Sînt, în mod esențial, acțiuni provocatoare, dar care dispuneau de sprijinul unor contingente ale armatei. În paralel, au constituit un ajutor în opera de creare a unei mișcări sindicale „albe”: înainte de intervenția de la Regie, 183 de muncitori și funcționari, dintr-un total de o mie de angajați, au semnat actul de constituire a unui astfel de sindicat. - Francisco Veiga, Mistica Ultranaționalismului: Istoria Gărzii de Fier, 1919-1941, ed. II, Editura Humanitas, 1995, p.48.

- ^ Apoi, avînd în vedere că studențimea nu era un adversar prea serios în comparație cu feroviarii, și-au mutat ofensiva în afara sălilor de curs. Întrerupeau spectacolele de teatru cu subiecte insuficient de „patriotice” și ardeau în plină stradă beretele rusești ale studenților de stînga. Curînd presa de această tendință a devenit un obiectiv prioritar; grupul a molestat reporteri și, în primăvara lui 1921, a distrus rotativele ziarului socialist Lumea și patru sute de exemplare ale ziarului au fost arse în plină stradă. - Francisco Veiga, Mistica Ultranaționalismului: Istoria Gărzii de Fier, 1919-1941, ed. II, Editura Humanitas, 1995, p. 52.

- ^ Un alt membru al guvernului a declarat că directoratul minelor din Lupeni este în mare parte responsabil de calamitate. Acesta a spus că directoratul a respins pur și simplu toate cererile minerilor, fapt care adesea nu se justifica, aceștia limitându-se să declare doar că minerii sunt infectați de comunism. […] În București se crede că membrilor liberali ai directoratului minelor din Lupeni le convine situația dificilă în care a fost băgat guvernul de acțiunea armatei. - "RIOT DEATH TOLL RISES AT RUMANIAN MINE: Number of Strikers Killed by Soldiers, First Put at 16 Now Said To Be 40", Special Cable to THE NEW YORK TIMES. New York Times (1923-Current file); Aug 8, 1929; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times (1851-2009), pg. 25.

- ^ Minele Lupeni aparțin unui grup de bănci liberale iar unul dintre directori este Tătărescu, fostul ministru liberal de interne. - "RUSH DEAD STRIKERS TO GRAVES IN CARTS", Wireless to THE NEW YORK TIMES. New York Times (1923-Current file); Aug 10, 1929; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times (1851-2009), pg. 3.

- ^ Un cordon de militari înconjoară spitalul în care se află mai mult de 2oo de răniți, în timp ce mai multe mii de muncitori care s-au adunat afară au fost alungați cu baionetele. - "RUSH DEAD STRIKERS TO GRAVES IN CARTS", Wireless to THE NEW YORK TIMES. New York Times (1923-Current file); Aug 10, 1929; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times (1851-2009), pg. 3.

- ^ Masacrul minerilor din Lupeni în 1929. The New York Times: „Scene sfâșietoare. Peste 20 de cadavre au fost puse în care de bălegar și duse în grabă la groapă”, 5 august 2016, Daniel Guță, Adevărul, accesat la 12 septembrie 2016

- ^ Cadavrele au fost puse în sicrie rudimentare și încărcate pe căruțe de cărat bălegar care au fost furnizate la ordinul directoratului minelor. Când au apărut carele și sicriele au fost încărcate s-au făcut auzite lamentații amare, cortegiul fiind îndemnat de militari să grăbească pasul. Mulțimea imensă adunată lângă cimitir a fost împinsă înapoi mai multe sute de metri, și la patru ore după înhumarea morților o companie de infanterie încă mai păzea cimitirul în poziție de tragere. - "RUSH DEAD STRIKERS TO GRAVES IN CARTS", Wireless to THE NEW YORK TIMES. New York Times (1923-Current file); Aug 10, 1929; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times (1851-2009), pg. 3.

- ^ După înmormântare, ofițeri precedați de toboșari, au citit un ordin prin care se impunea starea de asediu după ora opt seara, ordonând ca toată lumea să fie în casă la acea oră, deși era o seară sufocantă. Toate hotelurile și restaurantele, inclusiv cele ale stațiunii, sunt închise, iar vânzarea de băuturi alcoolice este interzisă până la noi ordine. […] Există știri despre soldați care caută cadavre în păduri, întrucât mulți din cei grav răniți au fugit panicați după deschiderea focului. N-au fost găsite alte cadavre, dar 25 de mineri încă lipsesc de la căminele lor. […] Continuă să se mai facă arestări și trenuri cu trupe încă mai sosesc în regiune. - "RUSH DEAD STRIKERS TO GRAVES IN CARTS", Wireless to THE NEW YORK TIMES. New York Times (1923-Current file); Aug 10, 1929; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times (1851-2009), pg. 3.

- ^ Cele două mișcări de extremă dreaptă au escaladat poziții luptînd împotriva acestui adversar „solid” în serviciul unor interese socio-economice care aveau nevoie temporar de ele; astfel, deși apăruseră cu foarte puțini ani înainte de mișcarea lui Codreanu, au cîștigat curînd un ascendent față de aceasta care, dimpotrivă, nu a întîlnit la stînga decît un gol." - Francisco Veiga, Mistica Ultranaționalismului: Istoria Gărzii de Fier, 1919-1941, ed. II, Editura Humanitas, 1995, pp. 75-76.

- ^ Totuși, conducătorii PCR erau conștienți de pericolele unei beligeranțe active și au menținut o atitudine mai degrabă pragmatică, ceea ce nu ne permite să le atribuim importanța hotărâtoare la Lupeni și în alte conflicte ale epocii, cum o făcea istoriografia românească oficială din perioada comunistă.(Pe atunci comuniștii traversau o perioadă de paralizie cronică, rezultat al loviturilor primite și al slabei capacități de a intra în legătură cu masele muncitorești. Mai mult, după acuzațiile ulterioare ale lui Béla Kún, liderii de atunci s-au abținut să sprijine activ greva, pe care o considerau rezultatul acțiunii unor provocatori. (Vezi Robert R. King, op. cit.; vezi p. 18 și 22. G. D. Jackson, op. cit., pp. 257-265.) - Francisco Veiga, Mistica Ultranaționalismului: Istoria Gărzii de Fier, 1919-1941, ed. II, Editura Humanitas, 1995, p. 105.

Legături externe

[modificare | modificare sursă]

Wikipedia (en/ro)

(Archives 1944-1989)

▪ Collection: Videos of Jiu Valley miners – 1950 | Romanian Communist Party

▪ Collection: Photos of Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej and Nicolae Ceauşescu with Jiu Valley miners (1944-1977) | FOCR

Fototeca online a comunismului românesc | Arhivele Naţionale ale României şi Institutul de Investigare a Crimelor Comunismului în România

▪ Collection: Historical photos of Jiu Valley miners | PMM

Petrosani Mining Museum

-220x150.jpg)

![Miners in Lupeni coal mine. [photo: Petrosani Mining Museum]](https://jiuvalley.org/wp-content/uploads/gdrive/Archives-Petrosani_Mining_Museum/3-lupeni3-220x150.jpg)

![Miners in Lupeni coal mine. [photo: Petrosani Mining Museum]](https://jiuvalley.org/wp-content/uploads/gdrive/Archives-Petrosani_Mining_Museum/4-lupeni2-220x150.jpg)

![Miners in Lupeni coal mine. [photo: Petrosani Mining Museum]](https://jiuvalley.org/wp-content/uploads/gdrive/Archives-Petrosani_Mining_Museum/8-lupeni1-220x150.jpg)

![Miners in Lupeni coal mine. [photo: Petrosani Mining Museum]](https://jiuvalley.org/wp-content/uploads/gdrive/Archives-Petrosani_Mining_Museum/7-lupeni1-220x150.jpg)

![Miners in Lupeni coal mine. [photo: Petrosani Mining Museum]](https://jiuvalley.org/wp-content/uploads/gdrive/Archives-Petrosani_Mining_Museum/6-lupeni1-220x150.jpg)